Earlier this year we finished up a series at church exploring the theme, “Deeper into Pain & Suffering”. As part of it, I had the privilege of preaching 5 talks through the book of Job. It was a challenge covering 42 chapters as a church but we made it, and God spoke to us deeply through it!

I was thankful for the time and opportunity last year to translate much of Job from the original Hebrew during our nationwide lockdown, which helped immensely with feeling the beauty of the text and the weight of Job’s story. The most helpful commentaries I found were Christopher Ash’s “The Wisdom of the Cross” and Lindsay Wilson’s Two Horizons commentary on Job. Kirk Patston’s Wisdom Literature lectures from our Bible College were also a real help, especially for Job 1-2. Also helpful is Daniel Estes’s Themelios essay on preaching Job in the 21st century.

For preachers, bible study leaders, keen readers, here’s a couple of thoughts and exegetical gems in no particular order:

- In chapter 1-2, the original Hebrew text uses the word brk (“to bless”) where English translations say “curse” (a different word in Hebrew). It’s worth letting readers decide whether it’s a euphemism (“to curse”), or preserves an ambiguity about how Job responds to suffering throughout this book. I chat more about it here.

- The biggest mistake when preaching Job is to make him the moral hero we should emulate and to end with “be like Job” (but we can’t!) Job’s character is not flat and stoic – he responds in worship (ch1-2), lament (3), and even protest throughout the book. Job rather is a type of Christ, the Suffering Servant: Job’s howls (3:24) foreshadow Christ howling on the cross; his lousy friends contrast with the Friend for sinners; evil and chaos seems wild and untamed (Job 38-41) but God sovereignly uses the greatest act of suffering (the cross) for the greatest good (our salvation). The Christ-centred preacher or teacher should take each theme Job uncovers, and thread them to their ultimate conclusion at the cross of Christ. Because ultimately, the gospel gives us what we need to keep walking with God through our pain and suffering.

- Job’s lament in chapter 3 is so powerful and counter-cultural (although more recently acceptable in light of “It’s OK to not be OK”). So much so that I think it’s worth setting aside a whole service to focus on it. We even shaped the service differently by having the whole service a time of lament and reflection. Our worship team led us through songs like “Is He Worthy?” and “Though You Slay Me”, a reading of Psalm 22, and a powerful testimony of suffering. It was a different but unforgettable service.

- Most of us get bogged down in the debate between Job and his friends. In essence, the logic of Job’s three friends is this: 1) God is wise + sovereign; 2) I’ve seen wicked people suffer; 3) Since you’re suffering, you must have done something wicked; 4) So repent and be good then God will bless you. What’s scary is how “truthful” they sound (and how similar to prosperity preaching!), yet how much they miss.

- If there was space for another sermon, I would have taken Job 26-31 (Job’s final arguments) as a standalone sermon – I think Daniel Estes is right to call Job 28 “the literary integrative center for the book”, and these chapters are where you get Job’s arguments in summary form. Some have suggested chapter 28 as a later addition, but three things go against it: 1) The “he” in Job 28:3 isn’t otherwise introduced, suggesting it’s still the “wicked person” from the previous chapter (27:13); 2) There’s shared vocabulary with Job’s other words, e.g. “gloom” and “thick darkness” like chapter 3; 3) In the Masoretic Text (our primary early copy of the Hebrew Bible) there’s no unit break between the end of chapter 27 and the start of 28 – the text continues.

- Christopher Ash helpfully points out that both Elihu and God offer responses to Job’s agonising and protesting. So we looked at them both together as answers to the two perennial questions of human suffering: “Why did this happen?” (questioning God’s wisdom) “How is this fair?” (questioning God’s justice). This gives you a way to naturally address the issue of theodicy from the text itself. It’s unusual for most preachers to separate Elihu from the other friends, but the text itself does, and I was convinced by Christopher Ash that this minor character offers good (if stern) wisdom that’s in line with Yahweh’s later response.

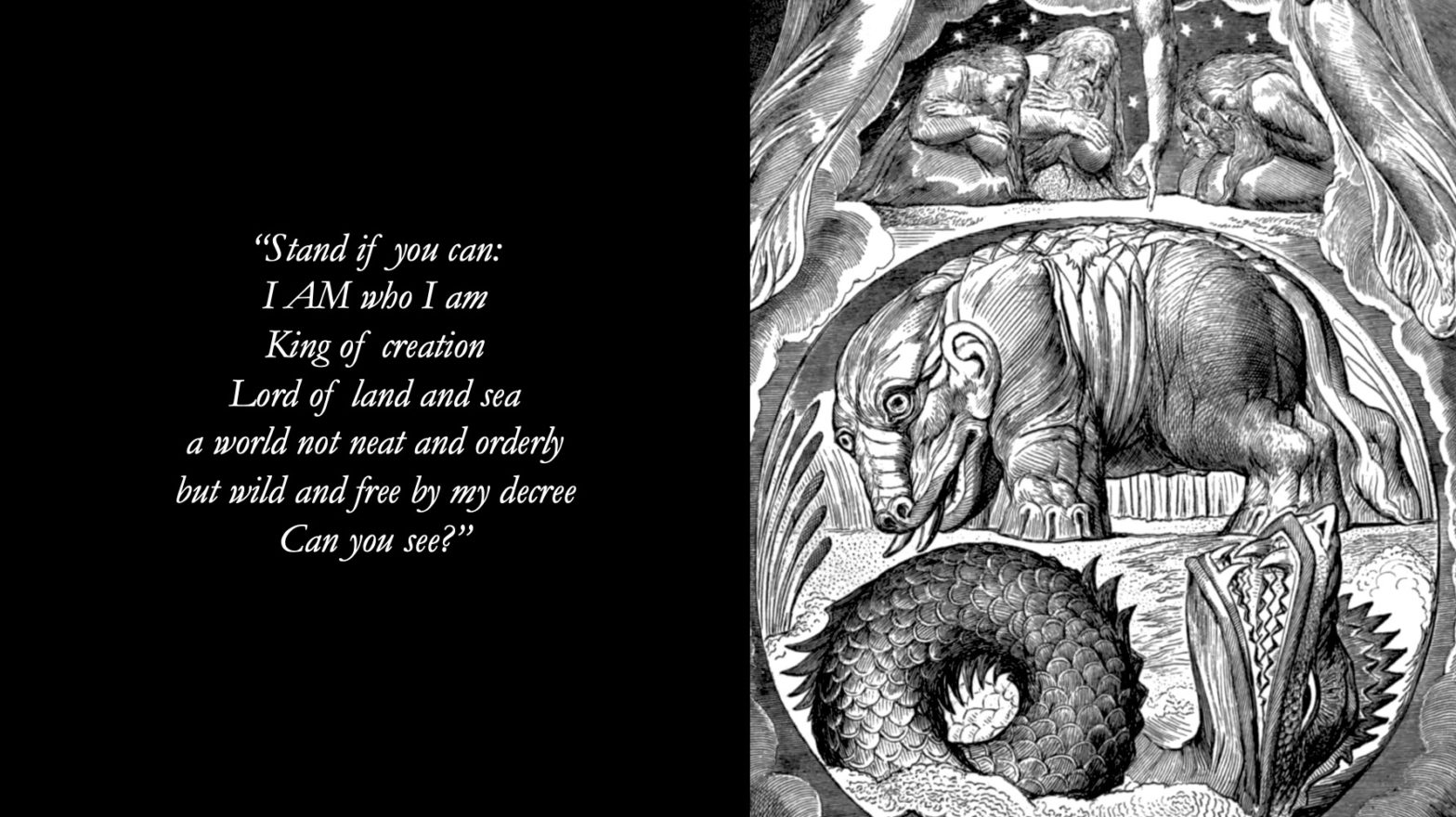

- In Job 38, God responds to Job using similar creation language and imagery of light and dark that Job earlier used when he laments and curses the day he was born (chapter 3). This shared language tells us that God is responding to Job’s laments and protests, and not just ignoring them.

- Job in the epilogue (chapter 42) is different to Job in the prologue (ch1-2) and the way he’s changed needs to be brought out: both the obvious: “My eyes have seen you” and the subtle (Job acting with grace and generosity by naming his daughters beautifully and leaving them an inheritance).

If you’re interested, you can hear the talks from Job here. I’m happy to share other resources I found helpful if you ask me personally.