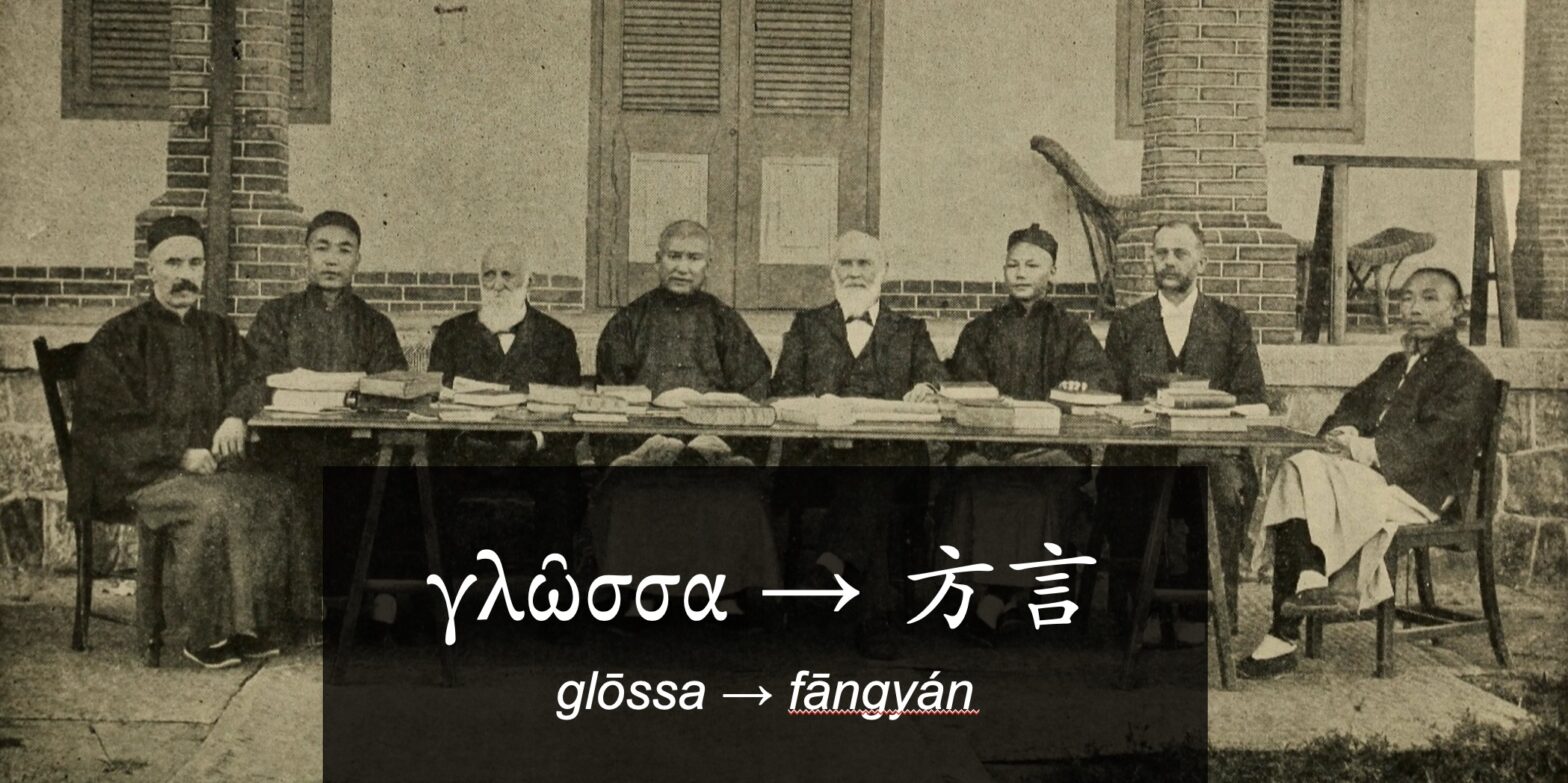

When translators of the Chinese Union Mandarin Version of the Bible first published the New Testament in 1907, they chose 方言 (fāngyán) to render the word γλῶσσα (glōssa) throughout 1 Corinthians 12-14. What does the word mean exactly? How can we encourage each other to “speak in tongues” more fruitfully, particularly in bilingual and multilingual church contexts?

Thanks to the team at MDPI, some long-form thoughts of mine on this topic have just been published in their Religions journal: https://mdpi.com/2691920.

The subject of this paper was inspired by our church’s cross-cultural journey through 1 Corinthians last year. (While I am pursuing postgraduate studies in New Testament theology, my PhD thesis will focus on delimitation criticism, a different area of Biblical studies). I’m grateful to the attendees at the 2023 Aotearoa New Zealand Association for Biblical Studies conference for the constructive feedback, my PhD supervisor for supporting this research tangent, and to friends, family and fellow scholars who critiqued and improved my (still imperfect) musings significantly.

If you’re interested, I’ve quoted the abstract of this paper, and summarised some practical applications below:

“…What did the Apostle Paul mean exactly when saying to Christians in Corinth: “I give thanks to God that I speak in fangyan (方言) more than you all” (1 Corinthians 14:18)?

Debates regarding Chinese Christian terminology are as old as the task of Bible translation in China, with no example more prominent than the “Term Question” (i.e., what Chinese term most suitably expressed “God”)… At stake when a Christian addressed “God” as shangdi (上帝) or shen (神) was not just a stylistic preference, but “whether Chinese were monotheists, polytheists or pantheists; whether there was the belief in Creation; whether the Chinese had the “idea of God”; what exactly was the nature and content of Chinese religion”, and more (Eber 1999, p. 135).

This paper presumes that exploring the fangyan question—what precisely should be meant by this biblical term—also has an important role to play in shaping Chinese Christianity today. By engaging with both the biblical text and its Chinese translation, I will argue that understanding Paul’s instructions regarding γλῶσσα/方言 within the context of a multilingual Christian worship culture strengthens the definition of γλῶσσα as languages used and understood among inhabitants of first century Corinth, and may offer more fruitful and relevant application to religious communities like it today…”

After arguing from a close reading of 1 Corinthians 12-14 in Biblical Greek, Mandarin and English, I try to point out the similarities between first-century Corinth’s cosmopolitan and multilingual setting and the many diaspora Chinese churches today. From there, I suggest three main areas of application when we read glōssa/fāngyán as human languages Paul and the Corinthian church knew and spoke:

- Translation and explanation during gathered worship. Diaspora churches with first- and second-generation members should recognise the problem of compartmentalisation between high and low varieties of language during their worship services. For example, in most Chinese churches it remains commonplace for the Mandarin CUV translation (now over 100 years old) to be preferred in readings, prayers, and liturgy, even if the preaching and singing are conducted in an entirely different vernacular such as Cantonese, present-day Mandarin, or English. However, without translating “formal” varieties of language into a “common tongue”, church members risk become engaged in prayer that is cognitively unfruitful as Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 14:14. Multilingual and multigenerational Chinese churches in particular should prioritise and pray for Spirit-empowered wisdom, seeking ways to translate and retranslate for each other so that everyone is edified when meeting together.

- Global missions. Understanding glōssa/fāngyán with a multilingual Corinthian lens may also help to reshape the Chinese church’s global missions strategy. Despite ongoing opposition, today there are “myriads” of Chinese missionaries retracing either the ancient Silk Road or today’s Belt and Road in order to fulfil the “Great Commission” (Matthew 28:19–20). Could they benefit from praying for and seeking the grace gift of speaking in other known languages? Even within China, there remains a pressing need for Mandarin-speaking churches to consider the linguistic needs of the millions of “minority” people groups whose “dreams and visions” are shaped through myriads of fāngyán found throughout the country. Returning to a “missionary-expansion” understanding of the term fāngyán may serve the needs of these overlooked ethnolinguistic groups.

- “First nations” language and culture. Paul’s instructions aren’t limited to multilingual worship contexts in Chinese churches. In many Western countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA, there is a growing awareness and practice of incorporating the language and culture of indigenous or “first nations” people into the life of the church. While speaking in indigenous glōssa/fāngyán adds richness and diversity to Christian worship, Paul’s advice as a multilingual practitioner himself is to conduct it with sensitivity to those of different linguistic abilities and an attitude of love.

For those with the courage to wade through all 6000 words of the article, I’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback!

—————–

1 Corinthians 14:39-40

ὥστε, ἀδελφοί μου, ζηλοῦτε τὸ προφητεύειν καὶ τὸ λαλεῖν μὴ κωλύετε γλώσσαις· πάντα δὲ εὐσχημόνως καὶ κατὰ τάξιν γινέσθω. (“So then, my brothers and sisters, be zealous to prophesy and don’t forbid speaking in glōssa; and let all things be done with beauty and order.”)