Cheryl and I finally broke our No-Netflix policy in our household last Friday night to check out The Social Dilemma. It’s a docudrama filled with former employees of big tech companies confessing their involvement in shaping how tech giants like Google, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and others operate today. In a nutshell, they warn us: social media is designed to manipulate users, and it does this through perfectly curating our online experience to maximise your engagement for their growth and monetisation. These fears are personified through real-life montages of democracies falling to their knees, infographics correlating the rise of social media use with dark metrics, and a fictional dramatisation of a middle-class family that’s manipulated and torn apart by social media. (Trigger warning for Kiwis: there’s a few seconds of the Christchurch shooting footage).

The documentary warns viewers how manipulative social media has become, how it crafts an addictive and bespoke world for us to benefit advertisers (“surveillance capitalism”), how seemingly useful features like nudges and notifications are designed to build the “attention economy”, and finally calls for reforms and unity to build better, “humane tech”. Both of us learned a lot from its presentation and were challenged to evaluate how connected we really needed to be each day to our online networks. But while The Social Dilemma raises important questions and makes plenty of good points, I think it still misses the mark in a few ways.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67414332/200787_1_1100.0.jpg)

Firstly, The Social Dilemma casts blame in only one direction. In the opening scene, the interviewer asks the question: “What’s the actual problem here?” We hear from interviewers that programmers created things like “swipe to refresh”, “Recommended videos”, the “Like” button, and eventually twisted them for greedy, nefarious purposes. Time after time, the blame is thrown at “the companies” or “the advertisers”. But there’s little mention of our hearts and how we as users are complicit in the social dilemma. The blackness isn’t just inside the walls of Matrix-like datacentres churning out algorithms that lead us astray. The blackness is also in my heart as I post photos to fish for likes and hearts, or as I let loose a comment for the adulation of others watching, or as I mindlessly scroll down for pleasure in moments too small to truly satisfy. Social media may be particularly effective manipulative tools, but we who use them are not innocent avatars. We want to be liked, for our name to be great (even if it’s among our friends), we want to be right in the eyes of others. And too often we do this at the expense of loving God, and loving our neighbour (Mt 22:36-39). Without a Christian worldview, the blame game is easy but incomplete. When we as “users” are addicted, it isn’t just Facebook’s fault — we need to examine our own hearts and confess any deceitful way in us too (Ps 139:23-24).

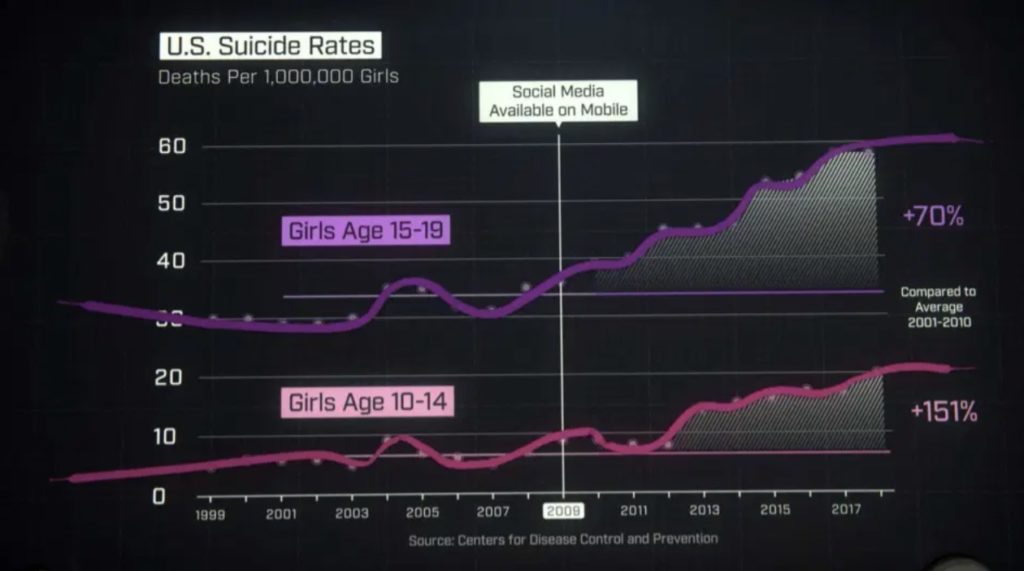

Secondly, The Social Dilemma evangelists weave story and statistics in unhelpful ways. For example, in one scene, a teenage girl sends out a selfie, is teased for her big ears, and sheds a tear while evaluating her self-worth in a mirror. It’s followed by a smart infographic charting an increase in suicide rates among teenage girls in the US, which not-so-subtly plonks down the fact that 2009 was when social media became available on mobile.

But how about if I plonk down on the same graph: “Barack Obama became US President in 2009”? Or “Michael Jackson died in 2009”? Did those events lead to an increase in youth suicide among US teenage girls? Of course not — because correlation doesn’t equal causation. Yes, there is a horrifying youth suicide problem that we need to address. And yes, there is robust research out there about the positive association between social media use and depression. But this kind of simplistic (and I think false) sleight of hand isn’t it.

Finally, The Social Dilemma presents too small a solution. There’s a lot of resonance when you hear the various interviewees close with advice of unplugging from tech and exploring the outside world more. Man does not live on screen time alone. God’s whirlwind reply to the suffering Job was to lift his gaze beyond his suffering to the grandeur of His majestic and untamable creation.

But the “solutions” segment of the documentary seemed fairly anticlimactic after all the problems it raised. Sure, they’re helpful tips — turn off notifications, limit devices for kids (we practice them ourselves). But what was telling was that no one in the film was able to articulate any internal, heart solutions to the social dilemma.

When Jesus of Nazareth conducted his public ministry, he criticised the religious leaders of his day for obsessing on external solutions, without examining their heart motives. They had a fixation on correct ritual practices down to the exact type of herb to tithe, and revelled in public displays of piety – yet neglected what Jesus called “weightier matters of the law” (Mt 23:23) like justice, mercy and faith.

When describing his former addictions to a Pharisaical life, the Apostle Paul describes his achievements, puts them in the rubbish column (Phil 3:8) and replaces it with the “surpassing worth of knowing Jesus Christ our Lord”. It’s not enough to remove our social dilemma — we need something better to fill its place. The Christians who I observe using social media in helpful and edifying ways seem to be the ones who are Spirit-filled and satisfied in God. They demonstrate what Thomas Goodwin calls the “expulsive power of a new affection”.

The ultimate answer to our social dilemma, therefore, must be the gospel — Jesus Christ himself. No one else can offer more than He does through His death and resurrection. In Him we can turn from relying on social media for our joy, and discover an identity and purpose that can’t be downvoted, manipulated or auctioned off. So whenever you and I fall back into a social dilemma, remember that Jesus longs to be our true Joygiver, our first love, our #1 follow, and our source of endless delight.